Search:

Powered by

Website Baker

The Pacific House and Order Number 11 Historical Marker |

| Posted by The Muse (themuse) on Aug 25 2013 |

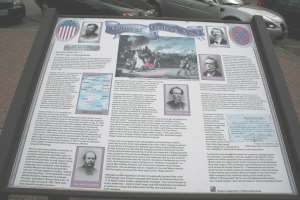

Brigadier-General Thomas Ewing, Jr. signed Order Number 11 in his headquarters which was located in the Pacific House at 401 Delaware Street in Kansas City, Missouri. Today, across the street from the Pacific House is a historical marker commemorating General Orders, No. 11.

The marker’s text …

General Orders No. 11:

The Revenge of Depopulation

The building in front of you (401 Delaware Street) opened for business in the spring of 1860 as the Pacific House Hotel, one of Kansas City's most up-to-date hotels. During the war years, the building was partially taken over by Union military authorities, and by 1863, was serving as the headquarters for the District of the Border under the command of Brig. Gen. Thomas Ewing, Jr. It was from his office in this building that Ewing issued the controversial General Orders No. 11 on Aug. 25, 1863.

General Orders No. 11 required that all inhabitants of the western Missouri border counties of Jackson, Cass, Bates, and the northern half of Vernon not living within one mile of specified military posts vacate their homes within 15 days (Sept. 9, 1863). Those citizens who could establish their loyalty to the Union with the commanding officer of the military station nearest their place of residence would be permitted to move to any military station in the District of the Border or to any part of Kansas except the counties on the eastern border of that state. Persons who failed to prove their loyalty were to move out of the district completely or be subject to military punishment.

General Orders. No. 11 is regarded by historians as one of the harshest measures ever taken by the United States government against its own citizens. The immediate cause for this stringent measure was retaliation for the bloody Lawrence Massacre, which had occurred on Aug. 21, 1863. On that morning, the notorious guerrilla chieftain, William Quantrill, and 450 of his followers rode into Lawrence, murdered over 150 mostly unarmed men, and burned the town. This horrifying incident was the culmination of guerrilla warfare along the border that had raged for several years. That Union commanders felt compelled to depopulate an entire region, encompassing an area approximately 28 miles wide by 90 miles long, reveals the desperate level of guerrilla warfare along the Missouri-Kansas border by late summer of 1863. It is also an admission of the inability of federal authorities to develop an effective anti-guerrilla strategy.

With too few troops available to eliminate or neutralize the guerrilla menace, Union strategists pursued the alternative policy of retaliation against the civilian population that harbored the guerrillas. In early August, Ewing wrote his superior, Gen. John M. Schofield, stating that since two-thirds of the families in western Missouri were kin to the guerrillas and were "actively engaged in feeding, clothing and sustaining them," several hundred of these families should be transported to Arkansas. This plan, embodied in General Orders No. 10, went into effect on Aug. 18, 1863. Three days later Quantrill attacked Lawrence.

Immediately, there arose in Kansas a clamor for revenge. Radical Kansas senator, James H. Lane, threatened to "lay waste to the border counties of Missouri and exterminate the disloyal people." Ewing was under tremendous pressure to take immediate action. His response was General Orders No. 11.

While perhaps less stringent than unrestrained vengeance by Kansas "Jayhawkers," General Orders No. 11 was, nonetheless, terrible enough in its own right. It caused great hardship and suffering on the civilian populations of the effected counties who were given just 15 days to vacate their homes and farms. There were descriptions of "refugees passing through...ill clad, often times barefooted, leaving their only shelter, and their only means of sustenance during the approaching winter - the crops now maturing - in numerous cases without money to buy food or pay rent going they know not wither." Long moving wagon trains of exiles in vehicles of every description drawn by teams of every variety, except "good ones," made their way out of the region. One federal officer declared, "It is heart sickening to see what I have seen...A desolated country and women and children, some of them almost naked. Some on foot and some in old wagons. Oh, God. What a sight to see in this once happy and peaceable country." This same officer, however, was a veteran of many clashes with Quantrill's band and thought Ewing's order one of the best that had been issued.

Perhaps the worst feature of the depopulation was that Kansas soldiers were used to assist in the enforcement of the order. These vengeance-minded troops did not overlook such a splendid opportunity to punish Missourians. Ewing's intention was that only hay and grain should be destroyed, but the Kansans ignored these instructions. Several men suspected of aiding Quantrill were summarily shot, and much pillaging of livestock and household valuables occurred. So many barns and houses were destroyed that in some areas the only standing structures were the charred chimneys of residences put to the torch. Such remainders came to be known as "Jennison's monuments," so named after Charles Jennison, one of the most notorious of the Kansas Jayhawkers. The devastation was so complete in Cass and Bates counties that the region was known for many years as the "Burnt District."

Although accurate figures do not exist, it is generally assumed that some 20,000 people were forced to evacuate their homes by General Orders No. 11. In Bates County, hardly a single family remained - the county became an empty wilderness - while in Cass County only 600 inhabitants were allowed to remain in a county that before the Civil War had a population of 9,794 residents.

While most hard-line Unionists considered General Orders No. 11 a military necessity to curtail guerrilla activity, the order aroused a storm of protest among moderate and conservative Missouri Unionists who regarded it as "inhuman, unmanly and barbarous." The best known of these critics was the celebrated Missouri artist, George Caleb Bingham. He had warned Ewing during a stormy meeting in the Pacific Hotel that if Ewing issued the order Bingham would make him "infamous with pen and brush as far as I am able." For the next 16 years, until his death, Bingham availed himself of every opportunity to assail Ewing for issuing the notorious order. He executed two versions of a painting entitled "Order No. 11," which depicted Ewing on horseback impassively presiding over a dismal scene of senseless murder and pillage committed on innocent civilians by heartless and bloodthirsty Kansas troops.

The public outcry against the harshness of the order soon led to a relaxing of its severe provisions. On Nov. 20, 1863, Gen. Ewing issued General Orders No. 20, which provided for a limited resettlement of the depopulated district by individuals who could meet a strict test for loyalty. In January, 1864, the District of the Border was reorganized and placed under command of Gen. Egbert B. Brown, who was one of the critics of General Orders. No. 11. He soon issued an order permitting persons to return to their homes in the district under more lenient requirements for proving loyalty.

The demise of General Orders No. 11 was one example of the inability of Union military authorities to devise a workable anti-guerrilla strategy. In 1864, Quantrill's band was back in Missouri, concentrating their operations north of the Missouri River in the central section of the state where they spread terror among Union sympathizers and continued to elude federal efforts to exterminate them.

Lacking the troop strength necessary for a massive campaign against the guerrillas, commanders were also unable to take effective action against the civilian population that sustained them. Public opinion simply would not support such drastic measures as the depopulation of an entire region. Still, as historian James McPherson has observed, such actions as General Orders No. 11 foreshadowed the total war practices that would be used in the eastern theater of the war during its final bloody year. Events in Missouri helped to move the federal high command to the conviction later put into words by Gen. William T. Sherman that "We are not only fighting hostile armies, but a hostile people," who must be made to "feel the hard hand of war."

Image Credits

-

The Pacific House photo by Dick Titterington

-

The General Orders, No. 11 historical marker photo by Dick Titterington

Dick Titterington, August 25, 2013.

Last changed: Aug 25 2013 at 9:54 AM

Back