Search:

Powered by

Website Baker

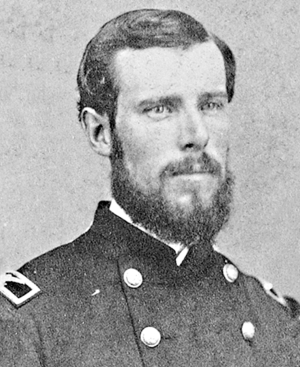

TMM Bio: Edward Francis Winsow |

| Posted by The Muse (themuse) on Oct 09 2018 |

|

Born in Maine, Edward Francis Winslow was sent west to Iowa to live with relatives. When the American Civil War began, Winslow raised a company which mustered in with the 4th Iowa Cavalry. Promoted to colonel of the regiment on the day Vicksburg fell, Winslow continued to distinguish himself for the rest of the war, rising to the rank of brevet brigadier general. following his death on October 22, 1914, two of his former comrades gave the following memorials to his memory. The first was by his former commander and subsequent business partner, Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson. The second was by his former sergeant major and adjutant in the 4th Iowa Cavalry, William Forse Scott. |

General Edward Francis Winslow: A Leader of Cavalry in the Great Rebellion

By James H. Wilson Major-General USA, Retired

By James H. Wilson Major-General USA, Retired

General Winslow died of heart failure at Canandaigua, New York, on Thursday, October 22, 1914, aged 77, and was interred there on the Sunday following. “Where the Oak falls there let it lie!”

He belongs to a group of American cavalrymen, including Upton, Long, Croxton, Winslow, LaGrange, Alexander, Minty and Miller, all remarkable for their military achievements as well as for their civic virtues. A glance at his history will show how richly he deserved and how fully he won the success and the honors that he gained.

The General was in the seventh generation and the direct male line from Kenelm Winslow and Magdalene Ollyver of Droitwich, Worcester, England, who came to Plymouth, with his brothers Josiah and Edward, on the first voyage of the Mayflower. A younger brother John, came on the second voyage and, after Carver and Bradford, ranked third among the signers of the Pilgrim Compact or Covenant of government.

The Winslows belonged to the English gentry and well-to-do class, and John, with his principal Pilgrim associates has passed into history as an actual leader in one of the greatest movements in the progress of human society.

The name of Winslow is an ancient one, the source of which is not known, but there is a town of Winslow tracing back to the Domesday-Book and is the name is now conceded to have been strictly English origin, although, like many others of the same period, it has also been claimed as Danish. It has had the usual variants and many different spellings, the principal ones of which are Weneslai, Wyncelaive, Wynceloe, and Winsloe, which in the lapse of time have settled down into Winslow, as it has always been used in America.

The English family wore coat armor, with the motto “Decoptus Floreo.” They intermarried with people of like rank, and many of them became distinguished divines and successful men in the various callings of life. A member of the family became almoner to Queen Elizabeth, who in turn became godmother to his son. Another was deep in the Gunpowder-Plot, while still another became one of the most distinguished physicians and surgeons of his day in Paris.

In America the Winslows have always intermarried with their own class, and the family, counting together the male and female lines, numbered in 1888 thirteen thousand three hundred and ninety. There have been from the earliest days, as might have been expected from such sources, ministers of the Gospel, professors, judges, doctors, surgeons, artists, musicians, contractors, engineers, writers, builders, sea captains, naval and army officers, admirals, generals and governors, belonging to both the male and female lines, and it may be safely assumed that wherever the name of Winslow found in the United States or Canada, its owners are of kin and all descended from the Winslows of the Pilgrim Fathers. It may well be claimed that no pedigree of greater distinction or of purer Anglo-Saxon blood than that of the Winslows can be found in American annals, and that no name stands higher in the list to which it belongs than that of the subject of this sketch.

General Winslow was the son of Stephen Winslow and Elizabeth Bass and was born at Augusta, Maine, September 28, 1837. He was seventh in direct descent from Kenelm, through Job, James, Benjamin, William and Stephen. He was educated in the common and high schools of his native place. Having business aptitudes of no mean order he early went west, to Mount Pleasant, Iowa, for the purpose of going into a bank about to he established at that place. His uncle was at that time building the State capitol at the city of Des Moines. This perhaps gave the young man's mind a different purpose. He soon became a railway contractor, and was fast rising into prominence as a masterful and enterprising man when the war for the Union broke out with the Southern states. In the midst of the excitement growing out of Secession he had married Laura Berry, the daughter of Rev. Lucien H. Berry, D. D., and Adilene Fay, of Boston. The young couple were just settling down to married life when the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter and, as if by magic, called the patriotic young men of the entire north to the defense of the Union.

Winslow was amongst the first to offer his services, and as Captain of Company F, Fourth Iowa Cavalry, encamped at Mount Pleasant, he at once began his career as a commissioned officer He was wholly without education or experience as a soldier, but his native intelligence and aptitude finely qualified him to receive the instruction given to the officers of the regiment by its Lieutenant-Colonel (Drummond), who was a cavalry officer of the Regular army, and later from the rough school of experience. He soon knew how to render useful and increasingly brilliant services in the field. Any one curious to know how discipline and soldiering were learned in those days by the green boys from civil life, should read the exciting “Story of the Fourth Iowa Cavalry,” by its Adjutant, William Forse Scott.

Winslow’s progress was rapid and his deeds were from the first inspired by an ardent ambition as well as by the prudent habits of the Pilgrim family to which he belonged, but the limits of this sketch will not permit the writer to recount them in detail. While they brought him to high rank and important command and enabled him to participate in some of the most notable events of the Civil War, as well as in some of the most remarkable undertakings which followed the country's recovery therefrom, they have yet to receive, in larger measure, the public commendation to which they are entitled. It does but scant justice to one who was a splendid soldier and a citizen of rare value to recount so briefly the principal events of his career; though any account would show that no ordinary man has been taken from us.

The Fourth Iowa was mustered into service late in November, 1861. Its first winter in service was a severe one, which delayed the regiment from taking the field. But, marching by the way of Springfield, Missouri, in the early spring of 1862, it joined Curtis's “Army of the South West,” at Forsyth, and took part in its demonstration on Little Rock, in which region, and at Helena on the Mississippi, where it finally took post, it was constantly engaged in operations against the enemy. This service lasted about a year and was filled with many vicissitudes, in which Captain Winslow displayed such activity and intelligence that he was made Provost-Marshal. And he was soon afterwards promoted to Major of his regiment.

General Grant, in the winter of 1862-1863 gathering his army for the campaign of Vicksburg, called for a regiment of cavalry. Through Winslow’s influence at district headquarters, his regiment was ordered to join Grant’s command at Milliken’s Bend, where it arrived at the end of April, 1863. It was attached to Sherman’s Fifteenth Army Corps, and Major Winslow soon won his confidence and support. The regiment thenceforth took an active part in all Sherman’s operations in Mississippi till Vicksburg invested. During the siege it was naturally kept on outpost, picket, patrol, reconnaissance, skirmishing and foraging duty; and as it was at that time the only cavalry regiment with the besieging army, its service was constant, toilsome and dangerous. It was during this most trying time that Grant’s Inspector-General made a close inspection of this hard-worked regiment and recommended that its Lieutenant-Colonel commanding, whom he found inefficient, should be discharged from the service. His resignation was tendered and accepted without delay; and on the 4th of July, the day Vicksburg surrendered, Major Winslow, without having been mustered in as Lieutenant-Colonel, took command as Colonel. He was on that day two months less than twenty-six years of age, but as he had been found to be the best officer of his regiment, his promotion received general approval. From that time forth, and so long as Winslow remained in that region, he was Chief of Cavalry with Sherman and McPherson, and continued as such till March, 1864.

During this period Colonel Winslow, with varying forces, commanded in most of the cavalry movements which took place in Central Mississippi, but these operations were usually limited in area and inconclusive because his command was far short of the strength it should have had; but he was always full of zeal and energy and was about the only cavalry officer in the Department whose reputation steadily rose with his experience.

It will be remembered that Grant’s victorious army, nearly a hundred thousand strong, was scattered after the surrender of Vicksburg, by the authorities in Washington, as was done the year before, after the Shiloh-Corinth campaign. Grant having received a severe injury by a fall of his horse, which practically disabled him for three months, Sherman had general command of operations in Mississippi, a command which fell to McPherson when Grant and Sherman were ordered to Chattanooga; and Winslow's cavalry was still further diminished and his difficulties in controlling the Big Black river region, for the protection of Vicksburg, correspondingly increased.

But, late in January, 1864, Sherman reappeared at Vicksburg and organized an expedition against Meridian, Miss., with a view to a possible advance upon Mobile. Early in February, with the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Corps and Winslow’s remnant of a brigade, numbering 1200, he moved rapidly on a direct line east, via Jackson. He had planned to bring a body of 10,000 cavalry from the district of Memphis under General Wm. Sooy Smith, to a junction with himself near Meridian.Winslow, covering Sherman s column, after much successful fighting, including the capture of Jackson by assault (the third time these horsemen had put the capture of that capital in their record), reached and captured the junction point, at Meridian, and then turned northward to unite his column with that coming from Memphis. But the redoubtable Forrest, now growing rapidly into fame as the great Confederate cavalry leader, by rapid marching and good management interposed himself between the National cavalry columns and, after defeating, finally drove General Smith, with his strong division, northward toward Memphis. Thereupon Winslow was ordered to rejoin Sherman on his return march to Vicksburg.

It was a short and rapid campaign, Winslow’s men doing all the exposed work, incessantly occupied, and successful at every step.

Meanwhile the time had come for the three-year regiments to reenlist or “veteranize,” and as Winslow’s regiment, under his active influence, was the first one in that Department to perform that patriotic act, it was, late in December, l863, granted a thirty days’ furlough, but as it could not be spared from the field the richly-earned reward was postponed till March, 1864, at which time Winslow and the veterans availed themselves of this opportunity to visit their homes. At the end of their leave they assembled at Saint Louis, where they were remounted and furnished with new arms and equipment. He then took them to Memphis, where the non-veterans left at Vicksburg and the recruits coming from Iowa had been collected in camp. He had now something more than thirteen hundred men and horses, a very large regiment for that time.

At Memphis the regiment was brigaded with the Third Iowa, under Colonel Noble, the Tenth Missouri, under Lieutenant-Colonel Benteen, and a four-gun battery of rifled artillery, all under Winslow, but he was still without the increased rank he had so richly won.

His brigade, now of ideal size, equipment and character, was joined with another into a division under Colonel George E. Waring, Jr., which reported to General Samuel D. Sturgis, of the Regular army, who was gathering a mixed force of eight or ten thousand men with which he was expected to move against and crush Forrest, then in northern Mississippi. Winslow’s brigade was the first to encounter the enemy with success, but the next day the whole force including the infantry became engaged. This was on June 10, 1861. Winslow held the right of the cavalry and successfully repulsed two charges of the enemy, when he was ordered to withdraw and make way for the infantry now arriving on the ground. In doing this his brigade was in reserve, and was not engaged again till the whole line, after a short and futile defense, was driven from the field with heavy losses in men and equipment.

In this emergency Winslow was ordered cover the retreat, through Ripley and Collierville to Memphis, which he did effectually; but the affair was a great and unnecessary disaster to the National arms, in which Winslow and his veterans were almost the only men to come out with honor. Their services and losses, both in men and horses, were heavy, but they not only covered the retreating infantry successfully, they also brought off the only two field guns that were saved from the enemy.

He was now placed in command of the division of cavalry, though still hampered in his service by the lack of the general’s rank which he had fully won. Then followed, in July and August, 1864, two campaigns in northern Mississippi, under Major-General A. J. Smith, against Forrest and Lee (Stephen D.), in which no opportunity was offered for any very effective operations by the cavalry.

At the end of August he was sent by the general commanding at Memphis, with all the men of his division whose horses were serviceable (about twenty-two hundred) to the relief of General Steele at Little Rock. Eight hundred were shipped by boat up the Arkansas River. With fourteen hundred Winslow crossed the Mississippi at Memphis, and made a long and tiresome march through the extensive swamps of southeastern Missouri and eastern Arkansas. This accomplished, he was ordered to join General Mower's belated expedition in pursuit of the Confederate General Price, who was moving northeasterly on Pilot Knob. Winslow's march was up the Black River into Missouri and thence, by a circular route, to Cape Girardeau, where he took steam-boats to Saint Louis. This exhausting and useless work, through no fault of his own, was done in the hot and sultry weather of September, and covered over three hundred miles through desolate, low and swampy country in which neither friend nor foe could find adequate subsistence. It did but little harm to the enemy and no good to Winslow or his men, though it taxed their resources and endurance to utmost limits. Mower himself was a fine soldier, and he gave Winslow great credit for the energy and skill with which he led the advance, and for the way he made the roads passable by rapidly constructed temporary standing or floating bridges, built with timbers taken from the neighboring plantations or cut from the adjacent forests.

After only two days at Saint Louis, with his command now reduced to the effective men of his original brigade, numbering hardly more than twelve hundred, he reported to General Pleasonton, regular cavalryman long in command of the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac, but lately transferred to the West, and, under his orders, took the road westward across the state towards Kansas City on the Missouri river. On the way he overtook another brigade, which by orders he joined to his own, and, with the united force, made a most difficult crossing of the Big Blue River in the face of the enemy. His advance was a desperate, but successful charge through an exposed ford obstructed by fallen and floating trees; but in the moment of victory Winslow was seriously wounded and forced to take an ambulance, though even that did not compel him to withdraw or to relinquish his command till darkness made all safe. His successor was Lieutenant-Colonel Benteen of the Tenth Missouri Cavalry, a most enterprising and gallant officer, who commanded the brigade during Winslow’s enforced absence.

Winslow was taken at once by ambulance to Kansas City, and thence by steamboat to Saint Louis. Here, at the end of November, lie was rejoined by that part of his brigade which he had had to leave in western Missouri, and thereupon resumed command although not yet fully recovered from his wound. Having hastened to ship his main body by steamboat to Louisville, under orders from General Thomas, now commanding at Nashville, in Sherman’s absence on the march to the sea, Winslow in person took boat for Memphis for the purpose of collecting the large number of his men, mostly dismounted, who had been left at that place, and sending them to join the others at Louisville, but before he could carry out this arrangement he was provokingly gathered in by his former commander, General Grierson, and ordered as second in command, with all the men he had collected, to accompany him on an expedition from Memphis, to destroy the northern section of the Mobile and Ohio railroad. This thoroughly accomplished, the column finally marched through the country to Vicksburg, Winslow thus reaching that famous place at the end of important campaigns for the sixth time.

Now he was at last free to unite the widely separated parts of his own brigade at Louisville, in obedience to the orders which made it a part of Upton’s division of the great Cavalry Corps then gathering at Nashville to confront Hood. Although he moved as fast as steamboats or railroads could carry him, neither he nor Upton, both energetic pushers, could reach Nashville in time to take part with the Corps in turning Hood’s flank and assuring that great victory.

Winslow’s brigade, after completing its remount, equipment and armament, at Louisville, was transported thence by steamboat down the Ohio and up the Tennessee, to Waterloo Landing, near the cantonment at Gravelly Springs, in northwestern Alabama. Here it joined the Corps and became the First Brigade of the Fourth Division (Upton's), destined soon to become known as one of the best of modern times.

But curiously enough Winslow had to go through another ordeal. Before Upton was permitted to assign him to the permanent command to which his services entitled him, he found it necessary to personally present him to the Corps Commander, for the purpose of assuring latter that he was not the Lieutenant-Colonel of the Fourth Iowa who had been reported at Vicksburg as incompetent. Fortunately a glance was sufficient for that, and he was not only assigned to the command of the brigade, but as there were no vacancies in the grade of brigadier in the entire army, he was brevetted to that in the Volunteers by the President, and by him assigned to command his brigade, in Upton’s division, with the full rank. That ended troubles and cleared his way to nearly a year’s most active and valuable service, which not only won for him the recommendation of those in immediate authority over him for the full rank of brigadier, but would have ensured him the rank of Major-General had the Confederacy not broken down in the full tide of his brilliant career.

In the reorganization of the regular army after the peace he was offered by General Sherman the rank major and finally that of colonel, but wisely declined both, to pursue the occupation of railroad builder and manager.

From the start of the campaign in Alabama and Georgia to the end of the war, Winslow’s career was most brilliant. Having, by his extraordinary marches and operations in nearly every part of the central Mississippi valley, learned his duties to the minutest details, there was nothing left for him but to lead his veteran brigade, including a four-gun battery, under the supervision of Upton, then the most accomplished division commander in the army. This he and his fellow brigadier, Alexander, did so well, that when it was all over Upton, although he had commanded both infantry and artillery in the Army of the Potomac with marked success, said he never knew what troops could do till he had led his cavalry division over the entrenchments at Selma and Columbus. After that and the running-affairs with Forrest, preceding Selma, he declared that there was no place in the Confederacy he could not ride into or over, and nothing he feared to attack except a man-of-war at sea. Winslow and his veterans, after a month of rest and drill, began their final campaign from the northwest corner of Alabama, with three divisions of the Corps numbering about fourteen thousand men, on March 22, 1865. After five days’ march towards the southeast, during which Winslow and the rest of the Corps threaded the forest and forded many rivers, his brigade leading, first came within reach of Forrest’s cavalry near Montevallo. While here it captured many supplies and destroyed the Red-Mountain, McIlvain, Bibb, Central and Columbiana Iron Works, five collieries, and the Cahawba Rolling Mill. With this important work done, the three divisions, except Croxton’s brigade, were united at Montevallo, and a spirited action occurred just south of that place, in which Forrest was outnumbered and driven rapidly from the field. The pursuit was immediate and pushed vigorously till night put an end to it.

The next day, April 1, the Corps pushed on to the south, LaGrange to take and hold the Centerville bridge on the Cahawba till Croxton, moving through Tuscaloosa, could reach it to rejoin the Corps, while the remaining two divisions, including Winslow's brigade, overtook Forrest at Ebenezer Church and drove him rapidly beyond Bogler’s Creek to Plantersville, where the main body bivouacked for the night. Forrest, completely overborne, retreated to the strongly fortified city of Selma, only eighteen miles further south. LaGrange rejoined the main column at Selma, but Croxton, after capturing Tuscaloosa, marched by a northern route to Macon in central Georgia, where he arrived a month later.

On Sunday, April 2, the day on which Richmond fell, the Cavalry Corps closed in on Selma, the principal manufacturing city of the Confederacy, a thousand miles southwest of Richmond. As it was completely covered by earthen fortifications of strong profile, with a deep ditch and a wooden stockade laid out on a bastioned line from three to four miles long and mounting thirty field guns with two of larger caliber, all manned by the home guards and Forrest’s cavalry, it was evident that a desperate struggle would ensue. Fortunately Adjutant Scott of Winslow’s staff had taken prisoner two days before an English engineer named Millington, who had on his person an accurate sketch of the works. With this as a guide the plan of attack was made during the morning of the advance on the city, and each division and brigade was assigned its proper place in the assault. Winslow took a route by the enemy’s extreme right, and, if successful, would cut off all retreat in that direction.

The attack was most unusual, by dismounted men from Long’s division in open order, supported by the remainder of each division, and was everywhere successful. The attacking force was fifteen hundred and fifty men and officers, hut the Union strength was about nine thousand five hundred men and twelve guns, while the enemy had inside the works a mixed force, estimated at from five thousand to seven thousand men and thirty-two guns, all under the personal command of Forrest. The first rush lasted not over twenty minutes, but before the mêlées which followed were ended darkness closed in. Twenty-seven hundred of the enemy were captured, but considerably over half escaped under cover of night. Winslow handled his men admirably, and carried the eastern part of the fortifications but little loss, and, being the ranking brigade commander who was not wounded, he was assigned that night to the command of the captured city the restoration of order, and finally to the destruction of public works, military stores and store houses, which were found there in great abundance.

Indeed no such capture had ever been made in a single action from the Confederacy, and the injury done was irreparable. The work of destroying the public property took place the following day, mostly under cover of darkness or in the rain, and was carried on with excellent system and with no avoidable loss to private property. During the occupation the pontoniers were building new pontoons for the extension of their bridge, so as to make it span the Alabama River, and thus enable the Corps to continue its march through Montgomery, towards a junction with Sherman, six hundred miles nearer the scene of Grant’s operations in Virginia.

Winslow being in command at Selma, with his staff and his old regiment, was naturally the last to cross the river, and to bring up the rear in the advance on Montgomery, the first capital of the Confederacy. Everyone expected another sharp action at that place, but the Mayor and principal citizens made haste to surrender without resistance. The Stars and Stripes were promptly raised over the stately Capitol about noon, April 12, 1865, and the victorious troopers, every man in the saddle, saluted the “Old Flag” and cheered as they passed on towards the Chattahoochee, about half way to Macon in central Georgia.

The ground was rapidly covered. At Columbus, another strongly fortified city, on the eastern bank of the Chattahoochee, Winslow in advance, waiting in the dark by arrangement till nearly 8:30 p.m., carried everything before him, in a rushing charge. His brigade was dismounted, every eighth man holding horses, while with the rest under cover of darkness, with no glimmer of light but the flash of the enemy’s guns, carried the works and bridges, and without halting pushed through them into the city. The prisoners taken in the heat of the fighting numbered more than the men engaged in the charge. The victory was not only complete, but one of the most remarkable ever gained by cavalry in modern times. The spoils were large and most important, for, after Selma, Columbus was the largest depot and manufacturing center of the Confederacy.

The defense was conducted by General Howell Cobb, who had been Secretary of the Treasury under President Buchanan. He had been aided by Colonel Von Zinken and the Colonel Lamar who had commanded the slave yacht Wanderer. Lamar was killed by a chance shot in the street. General Robert Toombs had also visited and counseled Cobb, but, with several hundred men, he escaped by train under cover of darkness before the action was ended. Those who remained behind made the best light they could in the blackness of night, but their struggle was in vain. All were captured, and Winslow, assisted by Noble and Benteen, under the supervision of Upton, was again placed in command, and succeeded in restoring perfect order before midnight. This remarkable affair took place on April 16, and was undoubtedly the last real battle of the war.

The next day Winslow completed the job by destroying one hundred and twenty-five thousand bales of cotton, twenty thousand sacks of corn, fifteen locomotives, two hundred and fifty freight cars, two bridges over the Chattahoochee, one navy yard, two rolling mills, the Gunboat Chattahoochee, the sea-going ram Jackson, besides all the foundries, iron works, arsenals, niter works, mills and factories. In addition he found sixty-nine pieces of artillery and large quantities of arms, military and naval stores of every kind, constituting the resources of the enemy.

This put the crown to Winslow’s military fame. Although there was no more fighting, he accompanied the cavalry into northern Georgia and shared in the honors of reoccupying Atlanta, finally placed him near the center of information and enabled him to play an important part in dispersing the last hostile forces in that region, and finally to advising in the dispositions which led to the capture of Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy. His military services through the campaign were of the highest quality, but having been fully set forth in the “Official Records,” as well as in Scott’s history of the Fourth Iowa Cavalry, there is but little need for further explanation.

It is, however, worthy of note that Winslow’s last remarkable performance was a transitionary one, during which he not only rebuilt the railroad which Sherman had destroyed from Atlanta to Chattanooga, but managed it so well after reopening it, as to move all the detachments and supplies for the Cavalry Corps and the suffering people, as well as to collect enough charges for freight and passengers, not only to enable him to repay the government all its expenditures, but to turn the railway over to its owners free of debt for repairs.

The Fourth Iowa Cavalry and its distinguished Colonel, after four years of honorable service, were mustered out with congratulatory commendation from all superior officers, at Atlanta on August 10, and discharged at Davenport, Iowa, on August 24, 1865, whereupon it immediately scattered for home.

It was his remarkable military service, including his railroad rebuilding, which led to Winslow’s selection immediately after muster out, to assist in establishing the National Express and Transportation Company through the United States, by which it was planned to find employment for the leading officers honorably discharged from both services.

Then General Winslow, after building fifty miles of the Vandalia railroad and selling his contract for the rest to the Pennsylvania Company, was selected for the construction of the Saint Louis and Southeastern and the Cairo and Vincennes railroads, which he carried through with such unusual speed that, after the great financial crash of 1873, he was called to the receivership and management of the Burlington, Cedar Rapids and Minnesota railroad for the next four years.

Meanwhile, under appointment by President Grant, he served as an expert inspector of the Union Pacific railroad on its completion and acceptance by the Government.

In November, 1879, he took charge of the Manhattan Elevated Railway, and after a year spent in unifying the control and management of the system, he accepted the Presidency and management of the Saint Louis and San Francisco and the Atlanta and Pacific Railway Companies, which he held for several years, to the satisfaction of all who were interested in them.

During this period he became President of the New York, Ontario and Western Railway Company and the head of the organization which in connection with that company constructed the railroad now commonly called the West Shore. In 1885 he severed his connection with those interests and thereafter devoted himself to the management of the Saint Louis and San Francisco railroad until his retirement from active business.

Winslow’s services as a soldier might properly be regarded as constituting a most heroic episode in the life of any American officer. An approximate calculation shows that his changes of station and his campaigns in the four years of his army service covered about 7,000 miles as the crow flies, and allowing for crooked roads and daily scouts and movements, it is more than probable that his official travel amounted to at least 14,000 miles, which could hardly have been surpassed by that of any other officer of his rank or period.

His subsequent civil employments cover about twenty-five years, during which he managed and controlled, or advised in the management of, many important lines and systems of railroad and received and disbursed many millions of capital. He spent his last twenty years mostly in Paris, where his handsome home was constantly open to his countrymen and friends. He gave much of his time to the American settlement and its interests, and especially to its church. He was the intimate friend of the pastor and congregation and helped liberally in every good work that either took in hand.

The diplomatic corps held him in high respect, and he had many friends among the foreign statesmen and public men, as well as among our own, who will mourn his absence and miss him from the places both at home and abroad that he graced with such unfailing amiability and benevolence.

While living in New York he became a member of the Union League, the Century, the Players and the Metropolitan Clubs, and later was elected a member of the Country and Automobile Clubs of Paris.

As he died without issue, leaving his fortune to his wife, and as no one has ever been heard to charge that it was excessive or unfairly got, it may be safely assumed that in every station of life “the work he did was better than the pay he got for it.”

Tribute of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion, Report of the Memorial Committee

By William Forse Scott, Late Adjutant Fourth Iowa Cavalry Veteran Volunteers

By William Forse Scott, Late Adjutant Fourth Iowa Cavalry Veteran Volunteers

Edward Francis Winslow was one of that splendid group of young cavalry generals whose tireless campaigns and daring feats, whose fearless assaults and brilliant successes, thrilled the army and the country during the last two years of the Great War. When at last, through costly experience, the right use of cavalry in the war began to be understood, when the test of actual trial had eliminated the incapable officers and developed the capable, when belated wisdom had established the Cavalry Bureau, and, under Stoneman and Wilson, an intelligent and energetic improvement in camps, arms, horses and equipment was achieved, when the cavalry divisions were at last used in cavalry campaigns and not as mere adjuncts to the infantry, then at once appeared that galaxy of mounted leaders—Sheridan, Wilson, Custer, Upton, Winslow, Gregg, and Alexander—the story of whose astonishing marches, crushing blows, and splendid achievements reads like a romance of knighthood. Sheridan and Gregg were but little past 30 years of age and all the others named between 25 and 30 when they were leading brigades, divisions and corps to brilliant victories.

General Winslow was born at Augusta, Maine, in 1837. He belonged to the distinguished family who have kept the name of Winslow high in the history of New England in every generation from the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth. He was a direct descendant of Kenelm Winslow, who was one of that sturdy little band who came over on the first voyage of the Mayflower and whose succeeding generations have supplied their country with governors, judges, generals, admirals and professional men in all fields.

Our companion did not at all lack the bold spirit of his ancestors. When he was not yet twenty he went to Iowa, then a new state, thinly settled, to make his own way. Here his zealous temperament was not contented with the banking business in which he was at first employed, and, though without either education or experience as an engineer, he undertook with confidence the building of railways, the first of which was just then projected for the state. This gave him room for action, and he was energetically pushing the work of construction when the war broke out.

He had then just been married, his wife being Miss Laura Berry, daughter of the Rev. Dr. Lucien H. Berry, a clergyman and educator, distinguished in university organization in the western states. But the call of his country was to him the supreme obligation. When the storm broke he sought release from his contracts as fast as possible while he was raising a company of volunteers. He enlisted as a private, was elected Captain, and with his men joined the Fourth Iowa Cavalry as Company F.

From the moment the regiment entered the field his service was extremely active, the first year being spent in southern Missouri and northern Arkansas, including the campaign of the Army of the Southwest against Little Rock early in 1862. He commanded in many cavalry movements in Arkansas, with a number of engagements, and was Provost-Marshal at Helena under a succession of the generals commanding there.

Promoted Major, January 3, 1863, he soon led two important expedition into the interior with prompt action and success. Then when General Grant in April. 1863, asked for a regiment of cavalry for his great campaign against Vicksburg, it was at Winslow's zealous request that the Fourth Iowa was chosen. It proved to be the only regiment of cavalry in Grant’s army until month after the investment of Vicksburg; and in the unceasing activity thus required Major Winslow was always at the front and never off duty. The regiment was assigned to Sherman’s Corps (the Fifteenth), though serving more or less with or for the other corps. The battle at Fourteen-Mile Creek, which struck directly upon his battalion, brought him especially to the attention of General Sherman, who from that time through life held him in high estimation.

During the siege of Vicksburg he was incessantly occupied, in command of part or the whole of his regiment, in protecting the rear of Grant’s army against incursions of rebel cavalry and the attempted advance of General Joseph E. Johnston to the relief of the beleaguered stronghold. In one of the engagements in this service he was severely wounded, but insisted very soon upon re¬turning to his saddle.

In this period, in June, 1863, he was promoted to Colonel, but the regiment had been so reduced in number by its strenuous campaigning that, under the army regulations, a colonel could not be mustered in. The difficulty was overcome by the intervention of General Sherman, who then appointed him Chief of the Cavalry Forces of the Fifteenth Corps, several other cavalry regiments having meantime joined from Memphis.

With this command he took an active and successful part on the northern flank of General Sherman’s column in the campaign against capture of Jackson, in July, 1863; and he commanded or took part in all the cavalry operations in central Mississippi during the autumn, with frequent minor engagements. In particular, under General Sherman’s immediate instructions, he commanded an expedition of 800 selected cavalry, in August, 1863, marching from the rear of Vicksburg to Memphis, via Granada, over 400 miles, destroying the railways and running north all the cars and locomotives, moving with such boldness and celerity as to mislead or evade the much larger forces of the enemy’s cavalry directed against him. This feat was highly commended by General Grant, then at Memphis.

The Fifteenth Corps being removed to Chattanooga, Colonel Winslow’s command became the Cavalry Forces of the Seventeenth Corps, under General McPherson, and continued its operations in central Mississippi, from Canton to Natchez.

Zealously promoting the reenlistment of his regiment for another three years’ as “Veterans,” he declined his right to release at the close of his first enlistment and remained with it in service to the end of the war, at the same time pushing successfully the recruiting in Iowa to fill up its diminished ranks. The Veterans being rewarded for reenlisting by a furlough of thirty days, he went with them to Iowa, thus finding his only respite from active service during the four years in the field, except when disabled by wounds.

In January, 1864, General Sherman returned to Vicksburg and organized his famous expedition to Meridian, with the purpose of destroying the railways centering there, as well as the arsenal and depots of supplies, thus crippling the enemy so far as to permit the transfer of more troops from Mississippi to increase the army in Georgia. Colonel Winslow was put in command of all the cavalrymen available—about 1200; and with that small force he kept the head oi Sherman’s army of 20,000, never halting, constantly driving the rebel brigades in front, with small, sharp engagements nearly every day for twelve days, finally taking Meridian in a brilliant charge.

Then he undertook a perilous march to the north, where the famous Forrest, with four brigades of cavalry, was opposing the advance of General Sooy Smith, who had been ordered by Sherman to bring two divisions of cavalry from Memphis to join him at Meridian. Finding that General Smith had not appeared in the country, though then ten days overdue (he had, in fact, been defeated by Forrest, near Okolona, and driven back, as was afterward learned), Winslow returned, rejoined Sherman, and guarded the rear and flanks of the army to Vicksburg.

He was then ordered to Memphis, where, during 1864, he commanded in succession, the Second Brigade of the Cavalry Division of the Sixteenth Corps, the Second Division of the Cavalry Corps of the District of West Tennessee and the Second Brigade of the Cavalry Division of the Department of Mississippi. This “Second” brigade was, in each case, Winslow’s original brigade, composed of the Third Iowa, Fourth Iowa and Tenth Missouri cavalry, which continued to be “Winslow’s Brigade” till the end of the war. With these commands he was in all the campaigns in north Mississippi against Generals Forrest and Stephen D. Lee.

On the disastrous defeat of one of these expeditions, commanded by General Sturgis, in .June 1864, Winslow’s brigade was the only one that fully held its ground; and in Sturgis’s disorderly retreat for a hundred miles it was the only rear guard, stubbornly resisting Forrest’s assaults with incessant fighting, and preventing the capture of the remainder of the army.

In September following, Winslow commanded a force of 1400 from his brigade, at the head of a division of infantry under General Mower, in the pursuit of the rebel General Price, who, with three or four divisions of cavalry, invaded Missouri from Arkansas and marched against Saint Louis and Jefferson City. This campaign he began by a march across the swamps from Memphis to Little Rock, where, by orders of General Steele, he was unreasonably delayed ten days and then required to march with Mower toward southeast Missouri on Price’s track. As Price was already a week ahead, the order for this march was an indefensible blunder. Mower’s and Winslow’s men and horses were worn out by nearly three weeks of laborious work in the hopeless pursuit over very bad roads in very hot weather. Both commands were compelled to abandon the direct march and go to Saint Louis by boats, from Cape Girardeau, to refit.

Winslow then, reduced in numbers to about 1200 but refitted and remounted, and separated from the infantry, marched to Jefferson City, then threatened by Price, and thence to Kansas City making the whole distance of over 300 miles within ten days. Overtaking Marmaduke’s division of Price’s forces in the evening of October 22, immediately attacked, pushing his advance in the darkness to the Big Blue river. The next morning, with the aid of a brigade of the Missouri State Cavalry then assigned to his command, he fought the brilliant battle of the Big Blue, crossing the river through obstructed fords under fire, wholly defeating Marmaduke, and driving his division off the field in disorder. Severely wounded and unhorsed at the moment of victory, he insisted upon finishing the day in pursuit of the beaten enemy while driven at the front in an ambulance. But he was then compelled to turn over the command, and was at once removed to Saint Louis for surgical care.

Meantime a special order of the War Department directed him to take his now famous brigade to General Thomas, at Nashville, for the impending great conflict with Hood. Accordingly, as soon as permitted to travel, he went to Memphis, to bring up to Louisville that portion of it which had not marched against Price. But General Dana, then commanding at Memphis, interfered, and required him to go as “Second in Command” to General Grierson, on an expedition for the destruction of railways and military supplies in northern Mississippi. This was very successfully done, in stormy winter-weather, the march taking twenty days, covering about 500 miles, and ending at Vicksburg, January 5, 1865.

Then at last he was free to execute his order to join General Thomas, and, although the defeat of Hood had already been accomplished, he at once took his men by boat up to Louisville, where the men who had been on the Price campaign had already arrived. His old brigade was thus again concentrated, and had the rare experience of two or three weeks quiet in camp, though the same time busy in preparation for the next campaign.

Now at last Winslow received some recognition of his great service by his promotion to Brevet-Brigadier-General “for gallantry in the field.” There being no vacancy in the grade of Brigadier-General, this brevet was conferred by special order of President Lincoln.

General Winslow’s brigade was then assigned to the Cavalry Corps of the Mississippi, commanded.by Brevet Major-General General James H. Wilson, as the First Brigade of the Fourth Division, the division under Brevet Major-General Emory Upton. It was still composed of the three old regiments, the Third and Fourth Iowa and Tenth Missouri cavalry, and now mustered about 2400 men and officers, all experienced and hardened in many campaigns.Early in February it moved on boats up the Tennessee, to Eastport, Mississippi, and there joined the Cavalry Corps. Here its division, with two others selected for the campaign, the First and Second, made final preparations for a great raid upon the Confederate interior lines.

Leaving Eastport in March, 1865, these divisions, 13,500 men, swept through Alabama to Selma and the Chattahoochee, wholly routed all of Forrest’s forces in a series of battles, took by assault, the heavily fortified posts of Selma and Columbus, destroyed all the iron-plants in Alabama and immense quantities of machinery and tools in war factories and foundries, artillery, small arms, ammunition, cotton, and other military supplies.At Selma General Winslow directed the mounted charge by his own regiment, after the dismounted men of the Second Division had rushed the fortifications, putting Forrest to rout and capturing nearly half his forces. He was thereupon placed in command of Selma, and directed the destruction of the great arsenals, foundries, machinery and shops there, the largest source of materiel of war then in the Confederacy.

In the last battle of the war, fought at Columbus, Georgia, April 16, 1865, his brigade led by himself, carried the enemy’s works, dismounted, in a daring assault by night; and by sheer audacity, captured the one remaining bridge giving access to the town at the moment the enemy were setting fire to it.

In recognition of these deeds he was placed in command of Columbus, and destroyed the navy yard with two armored war vessels, and the foundries, arsenals, factories and stores of supplies rivalling those at Selma in number and extent, being then the last place in the Confederacy producing war equipment in any quantity.

In the advance of the Corps upon Macon, and when ready to attack that city, April 20, 1865, all hostile operations were stopped by the news of the surrender of Lee at Appomattox and of Johnston and Beauregard at Raleigh. Thereupon General Winslow was sent, in command of the Fourth Division, to occupy Atlanta; and after scouting northwest Georgia with the most zealous activity in the hope of capturing the fleeing rebel President (a fortune which fell to another part of the Corps), he commanded that region, with headquarters at Atlanta, until August; rebuilt the great Chattahoochee railway bridge, a remarkable engineering achievement, in view of the rude materials used and the speed of the work, thus opening communication with the north and bringing in supplies for the Corps and the suffering people. During the summer he managed the civil administration m the large country occupied by his detachments, capturing or arresting meantime the rebel Vice-President Stephens, Stephen R. Mallory, Secretary of the Navy, Generals “Bob” Toombs and “Ben” Hill, lately United States Senators, and other prominent rebels.

Three or four months without further trouble gave final assurance of peace, and the volunteers were rapidly disbanded. In August, 1865, in the reduction of the army, the Veteran Fourth Iowa Cavalry, at the end of four years’ service, was mustered-out at Atlanta, and General 'Winslow led it home to Iowa.

In civil life he returned to railway construction, building in succession the Vandalia road, the Cairo & Vincennes, the Saint Louis & Southeastern, the West Shore, and the Saint Louis & San Francisco. He was Inspector for the United States of the Union-Pacific, and later Receiver of the Burlington, Cedar Rapids & Northern, and President of the New York, Ontario & Western, the Saint Louis & San Francisco, and the Atlantic & Pacific.

These arduous labors finally proved too much for a frame never robust; and he was compelled to cease active employment. He spent some years abroad for his health, and finally settled in Paris, making frequent visits, however, to America. A weakness of the heart finally carried him away, on October 22d last, when visiting Mrs. Frederick F. Thompson, a devoted family friend, at her home Canandaigua, N. Y., where lie now lies buried.

Though long absent from his country, he retained the deepest interest in its affairs and in the welfare of his American friends. Many of his compatriots living in or visiting Paris could tell of his untiring helpfulness and encouragement; only since his death is the number of his benefactions becoming known.

A soldier without fault, without failure, a citizen patriotic and self-sacrificing, a friend who never lost an occasion to prove his loyalty, and a husband who through long years brought unalloyed happiness to his wife, our departed companion was one whose services to his country have been of immeasurable value and in whose rare career we feel unbounded pride.

Source

Wilson, James H., and William F. Scott. General Edward Francis Winslow: A Leader of Cavalry in the Great Rebellion. New York: Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, 1915.

Last changed: Oct 09 2018 at 10:51 AM

Back