Search:

Powered by

Website Baker

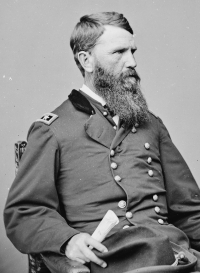

TMM Bio: Francis Preston Blair, Jr. |

| Posted by The Muse (themuse) on Nov 19 2018 |

Francis Preston Blair, Jr. was, and still is, a controversial figure in the history of the State of Missouri. Blair was an abolitionist who was instrumental in keeping Missouri in the Union at the beginning of the American Civil War. But Blair was no friend of African-Americans. He did not believe whites and blacks could live together in harmony. As a congressman, he argued for freeing the slaves and establishing a colony for them in South (Central?) America. His father was a power broker for the Republican Party and his brother served in President Abraham Lincoln’s cabinet. After the war, Blair broke with the Republican Party and switched to the Democratic Party. He unsuccessfully ran for the Democratic nomination for President of the United States, accepting the nomination for Vice President in the 1868 election, which was won by the Republican, Ulysses S. Grant. For a more complete biography of Blair, you should read William E. Parrish’s Frank Blair: Lincoln’s Conservative, published by the University of Missouri Press in 1998.

The Blair family in America has a distinguished history. It has JL numerous branches spreading over different sections of the country, yet the members of each have found important places in politics, law, science and literature. In the early history of Virginia, we find that James Blair, a native of Scotland, was a missionary of great learning and piety, who took such a deep interest in the colonies that he made a special visit to England, after the accession of William and Mary, to raise funds and obtain a patent for the erection of a college. He succeeded beyond his expectations, and on his return superintended the building of an institution which he named after the reigning sovereigns, and of which he was president nearly fifty years.

Another member of the family, named John Blair, was one of the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States appointed by Washington.

Another, James Blair, was a lawyer of considerable ability, who was born in Virginia, and practiced his profession for some time at Abingdon in that State. He afterward moved to Kentucky, and was made Attorney-General of that State. He was the father of Francis Preston Blair, known for so many years as the editor of the Washington Globe, and friend and adviser of Andrew Jackson. This eminent man, still living at Silver Springs, Maryland, at the advanced age of eighty-four, has probably seen more of American politics than any man living, and in nearly all the important movements of the past fifty years has had more or less to do.

His son, Francis Preston Blair, Jr., was no less conspicuous in public affairs; and, for the part he bore in. the Free-labor movement, and in defense of his country during the late civil war, will ever be held in grateful remembrance by all in Missouri who cherish the Union and love freedom. He was born in Lexington, Kentucky, February 19, 1821. When he was nine years of age his father moved to Washington, District of Columbia, to take charge of the Globe. Here his boyhood was passed in attending primary and preparatory schools, in which he made good progress in learning. His collegiate course was commenced at Chapel Hill, North Carolina, but, for good reasons, he afterward entered Princeton College, New Jersey, where he graduated with high honors at the age of twenty. Returning to Kentucky, he began the study of law under Lewis Marshall, but failing in health, he came to St. Louis on a visit to his brother, Judge Montgomery Blair. On his return to Kentucky, he completed his legal education at the Law School of Transylvania University. In 1843 he again came to St. Louis, to begin the practice of his profession; but his health was so delicate that he was forced to abandon all literary work, and take a trip to the Rocky Mountains to recuperate. This he did with trappers and traders, and in 1845 he accompanied Bent and St. Vrain to their fort in New Mexico, now Colorado, and remained in that wild and hostile country until the expedition under the command of General Kearney reached that region, when he joined the enterprise, and served to the end of it in a military capacity. In 1847 he returned to St. Louis, his health being completely re-established, and resumed the legal profession. The same year he was married to Miss Appoline Alexander, of Woodford County, Kentucky.

In 1848 his father gave him a liberal amount of money, which he invested judiciously and from it derived a competent and abundant fortune. This enabled him to devote a portion of his time to politics, for which he evinced a decided fondness. He became an active politician and a prominent leader of the Free-soil Party. In those days, making speeches against slavery on slave soil was somewhat dangerous; but Mr. Blair understood the temper and mettle of his opponents, and knew how much to say and when to say it. It was not long before his political enemies discovered that he was courageous, and would not be put down by threats. He was elected to the Legislature in 1852, and again in the following year. During his legislative term he made several speeches in favor of the Free-labor system, and aroused a strong sentiment against the exactions and encroachments of slavery. His bold words inflamed the Pro-slavery party, and created, of course, a strong feeling of hostility against him and his supporters; but he was not alarmed, nor deterred from the work he had undertaken. While the Free-labor movement made but little headway in the State, it gained a strong foothold in St. Louis, where the large German element existed, and in the spring of 1856 the Free-soil party was so well organized and drilled, under Blair's leadership, that it nominated a municipal ticket, and triumphantly elected it. The same year Mr. Blair was elected to Congress from the First District, and boldly advocated the doctrines of his party—but taking the position, which Henry Clay had taken years before, that the slaves, when emancipated, should be transported to Africa.

In 1858 Mr. Blair was nominated for re-election to Congress, but was beaten by J. Richard Barret, the candidate of the Democratic Party. Mr. Blair contested the right of Mr. Barret to the seat, and after a lengthy examination of the case, the House of Representatives referred the matter back to the people. A new election was ordered for the remainder of the term, and for convenience, the election for the next term was held at the same time. It resulted in the election of Mr. Barret to the short term, and Mr. Blair to the long term.

He was subsequently elected to the Thirty-eighth Congress, in which he served as chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs, and as a member of other important committees. His influence at this time, both in Congress and at home, was unbounded. A Southern man himself, a former slaveholder, and possessing many of the Southern traits of character, the cry of Abolitionist could not be raised against him, and he stood the most consistent promoter of anti-slavery doctrines in the United States. Says a recent writer: "His calm, argumentative manner in the debate even of an inflammable political question, amazed his adversaries, while his personal courage was so great that any attempt to overawe or intimidate him was labor lost."

In June 1860, at Mr. Blair's suggestion, a meeting of the Republicans of the State was called, to send delegates to the Chicago Presidential Convention. He was chosen as one of the delegates, and took an active part in the proceedings of that body. When a difficulty arose between the friends of Hon. Joshua R. Giddings and others, as to the propriety of adopting a certain resolution as part of the national platform, and the chairman of the Convention, Mr. Ashmun, had decided the question against the Giddings party, so that a division was imminent, Mr. Blair raised a point of order which brought the resolution fairly before the Convention again. This time it was so amended as to satisfy a majority of the delegates and still retain its force; and its adoption saved a split in the Republican Party.

On returning to St. Louis after Mr. Lincoln's nomination, Mr. Blair addressed a ratification meeting, held at Lucas Market, but was so much interrupted by the "roughs" of the Democratic Party, that he began to consider how similar scenes of violence might be prevented in future. His fertile brain conceived the idea of the "Wide Awakes," who were uniformed, provided with torches, and maintained order at Republican gatherings. The other party also formed clubs, known as "Minute Men," and collisions between these two parties were of frequent occurrence. The ''Wide Awakes" often accompanied Blair on his country electioneering tours, and prevented many a stoning which he and his companions would otherwise have received.

With the election of Mr. Lincoln, the war seemed inevitable, and General Blair was the first to perceive the necessity of enlisting troops. No man was so active in the movement as he. He was the Captain of the first company of Union soldiers enlisted in Missouri, and materially assisted in defraying the expense of providing the men with suitable arms and accoutrements. When companies multiplied and grew to regiments, he was as active as before, and was by unanimous consent elected Colonel of the First regiment of Missouri Volunteers. While these troops were being enlisted and armed, the rebels were collecting a force at Camp Jackson to attack and take the Arsenal and make use of the large amount of stores placed there. General Blair's quick discernment unearthed the plot, and acting on his advice, General Lyon moved several regiments of volunteers and companies of regular United States soldiers from the Arsenal and Jefferson Barracks, and captured the camp with all therein. The unfortunate killing of citizens at the close of the day was deeply regretted by General Blair, but the insults of the mob were so wanton and their firing upon the troops so unprovoked, that the latter could not be restrained and in fact were not considered blamable. General Blair was censured by some conservative Union men at the time for the part he took in the capture of Camp Jackson. They claimed that the State troops were legally organized and called into service by the Governor, and had no intention of joining in rebellion against the United States Government. But General Blair knew, and subsequent events developed the fact, that the encampment was a well-laid plot to get control of the State and to seize United States property General Blair nipped the conspiracy in the bud, and saved Missouri to the Union.

During the greater portion of 1861, General Blair's time was occupied in looking after the interests of Missouri. At his instance General Harney was removed from the command of the Missouri Department, because he thought the safety of the State and good of the public service required it; but when General Fremont, the successor of Harney, managed military affairs in a way that seemed to General Blair detrimental to the interests of the country, he demanded his removal also and secured it, notwithstanding a majority of the Germans, as well as a large number of prominent American Republicans, were in favor of Fremont's retention as Department commander. This act of securing Fremont's removal was the cause of a division in the ranks of the Emancipationists. Those who favored the immediate emancipation of slaves in the State, and were the strongest supporters of Mr. Lincoln's administration, became hostile to General Blair, and, notwithstanding past relations, both personal and political, denounced his action in unmeasured terms. He gained friends, however, from Conservatives, gradual Emancipationists and Democrats, and with the administration at Washington seemed stronger than ever. General Blair, in the meantime, continued to aid the cause of his country, both in the field and in the halls of Congress. Believing that he could be of more service to the Union cause in the army, he remained with his troops during the spring and summer of 1862, but later in the year he returned to St. Louis, and decided to test his political strength by offering himself again as a candidate for Congress. He made a strong canvass, and did not hesitate to deal hard blows against his old-time associates, who were now arrayed against him. Mr. Samuel Knox was the candidate of the Radical Emancipationists, opposed to him, and the official vote of the election gave Blair 4,743; Knox, 4,590; Bogy, Democrat, 2,536. The Radicals elected their legislative and county ticket. Mr. Knox subsequently contested Blair's right to the seat, and it was awarded to him. General Blair resumed his place in the army, having been promoted to the rank of Major-General of volunteers November 29, 1862, and determined to let political affairs at home take care of themselves. The breach that had been made in the Republican party of Missouri, however, was never healed so far as General Blair was concerned. He asked no quarter and would give none. His sentiments, so far as he expressed them, were against immediate emancipation, and his influence went to aid the opposition party.

At the close of the month of December 1872, an organized plan was put in operation for the capture of Vicksburg. Troops were accordingly sent up the Yazoo River in large numbers, under four experienced division commanders, and the whole expedition was under General Sherman's immediate control. General Blair commanded the First Brigade of the Fourth (Steele's) Division, and in the order of attack was given the right centre. When the command was given to advance he did so promptly, and made the assault on the enemy’s line. The Record says:

The first movement was over a sloping plateau, raked by a direct and enfilading fire from heavy artillery, and swept by a storm of bullets from the rifle-pits. Undauntedly the brigade passed on, and in a few moments drove the enemy fi-om their first range of rifle-pits, and took full possession of them. Halting for a moment, the brigade pushed forward and took possession of the second line of rifle-pits, about two hundred yards distant. The batteries were above this line, and their firing still continued. A prompt and powerful support was necessary to make the attempt to capture them. Simultaneously with the advance of General Blair, an order was given to General Thayer, of General Steele's division, to go forward with his brigade. He crossed the bayou by the same bridge as General Blair, and entered the abatis at the same point, and, deflecting to the right, came out upon the sloping plateau about two hundred yards to the right of General Blair, and at the same time. As he reached the rifle-pits, with a heavy loss, he perceived that only one regiment, the Fourth Iowa, Colonel Williamson, had followed him. After his movement commenced, the second regiment of his brigade had been sent to the right of General Morgan as a support. The other regiments had followed this one. Notice of this change of the march of the second regiment, although sent, had failed to reach General Thayer. With little hope of success he bravely pushed forward into the second line of rifle-pits of the enemy on the right of General Blair. Here, leaving the regiment to hold the position, he hurried back for reinforcements. Meanwhile, General Blair, vainly waiting for support, descended in person to persuade the advance of more troops. He and General Thayer both failed in their efforts, and were obliged to order their commands to retire. While General Blair was urging the advance of more troops, his brigade fought with desperation to win the way to the top of the crest. Meantime, a Confederate infantry force was concentrated to attack them, and after a sharp struggle, they were forced back to the second line of rifle-pits, when General Blair's order to retire was received.

The failure of the forces under General Grant to act in concert with those under General Sherman in this attack on Vicksburg, caused the latter to withdraw, and on January 2, 1863, the troops were embarked, and moved down to the mouth of the Yazoo River. Throughout this short campaign General Blair acted with great gallantry, coolness and prudence.

From this time until the final siege and capture of Vicksburg, General Blair was doing efficient service as a division commander. Whenever a difficult movement was to be made, he was selected to lead it, and when hard fighting was necessary his men were sure to be near. During the siege of the city, by order of General Grant, the division under Blair laid waste the country for fifty miles around, drove off the white inhabitants, burned the grist mills, cotton gins and granaries, and destroyed the crops. This course was distasteful to General Blair, but it was necessary in order to cut off the enemies' supplies and force capitulation, and he obeyed orders to the letter, his command acting as a “besom of destruction."

On the death of General McPherson, General Blair was advanced to the command of the Seventeenth Army Corps. He had, during the fall and winter of 1863, participated in the active and successful campaigns of Sherman in Tennessee, and with the opening of spring these successes were followed up by a further advance into the enemy's country. At the battle of Kennesaw Mountains, on the 27th and 28th of May, General Blair held the extreme left of General McPherson's line, and rendered important service against the enemy. The army under Sherman, though temporarily defeated here, soon recuperated, and following up the enemy prepared for a siege against Atlanta. The history of that siege is familiar to all. In the operations before that city, General Blair bore a most conspicuous part as commander of the Seventeenth corps. His discipline was perfect, his judgment never at fault, and his courage inspired all his comrades. In the celebrated "March to the Sea" under Sherman, Blair's men were always in advance, and always skirmishing with the enemy. They never went hungry if there was anything in the way to forage on, and for this reason were frequently accused of doing bold and wanton acts, but as their record for fighting was so good, their little eccentricities were overlooked by all good Unionists.

With the capture of Savannah, on the 22d of December, the winter campaign of Sherman's army closed, and with the opening spring of 1865 the war virtually terminated. At the close of the great campaign to the sea. General Blair returned to his old home in St. Louis, where he was received with the warmest demonstrations of friendship and affection by all classes of citizens.

In reviewing the career of this eminent man, we cannot do better than to quote a portion of the speech made by Colonel Thomas T. Gantt, before the State Convention at Jefferson City on the 10th of July 1875, when the fact of his death was announced:

Since 1848 General Blair has been always in public life. If a fault can be imputed to him it is that in his zeal for the service of the State he has almost culpably neglected the care of his own household. In 1848, by means of the investments which the liberality of his father enabled him to make in the rapidly-increasing city of St. Louis, he was possessed of a competent, nay an abundant fortune. He entered with ardor into public life. With a cool head, a warm heart and intrepid courage, he cherished as the dearest object of honorable ambition the wish to distinguish himself in the service of the State. He aspired to this service, looking to the consciousness of duty performed as a sufficient reward for the nights and days of toil which he devoted to its performance. Of course he was not indifferent to the fame that follows such performance: but for this fame, not for the vulgar and sordid remuneration which consists of the emoluments of office, he was more than willing to ''scorn delights and live laborious days." Devoting himself thus to the public service, he did not, in servile fashion, seek to accommodate himself to the prevailing prejudice of the community. Never was a man less of the time-server than Frank Blair. He entered upon the political arena when what was called the "Wilmot proviso" agitated the country. He thought he saw in the efforts of some statesmen a menace to the perpetuity of the Union. He scented this danger afar off, and while others considered his apprehensions imaginary, he denounced boldly and loudly the measures from which he augured the coming peril. Those who lived then and partook of the events of that day know well how little of the idle alarmist was Frank Blair. It required the highest courage to contemplate and to consider the threatened danger. It is the part of a timid man to shut his eyes and his ears to danger when it is distant and when forethought may provide against it, but to be bewildered and dismayed when it closes upon him. Frank Blair belonged to that heroic band whose fears and deliberations, whose doubts and misgivings, are confined to the council chamber, but are banished from the field of action. He looked forward to and took measure of the threatened calamity; he made provision against it, giving all credit for capacity to hurt, while it was yet too distant to strike; but when he was confronted by it all doubt had vanished, all deliberation had ceased. The time for council had passed, the hour of action had arrived, and to the demands of that hour he never had an inadequate reply. By reason of having considered exhaustively the proportions of an evil while it was yet distant, he was unappalled by its near approach, and thus events of the most startling nature never found him unprepared. What many attributed to the endowment of an almost miraculous presence of mind was really due to patient and laborious provision and preparation. Like another heroic man whose name stands for the admiration of preceding ages, he was 'Sævis in tranquillus undis' 'tranquil amidst tumult because he had dared to fear in tranquility.'

I have remarked upon the intrepidity of his character. There never was a man who took less counsel of his fears. If he was accessible to a feeling which Turenne declared to be a part of human nature, he never allowed it perceptibly to sway his conduct, and over and over again he distinguished himself by assuming and performing tasks from which, on one pretext or another, all others shrank. In his earlier political life, he led in an enterprise which was beset with obloquy and peril. For a long time he had very few followers. Those who sympathized with his views and avowed their sympathy, gave a conspicuous proof of their own courage: but all such will acknowledge that his leadership was never challenged. I will not dwell on the events of the years between 1852 and 1861; but, coming to the latter period, I think I may say that to him more than to any man living or dead, it is due that Missouri, and by consequence Kentucky, stood where they did in the eventful years that followed. I think also that he takes a shortsighted and imperfect view of our history who does not perceive that had these two States stood with Virginia in the terrible struggle that followed, the result of that struggle would have been widely different; and all who believe that it was a benefit to the whole country that it should exist undivided, must recognize a debt of immeasurable magnitude to Frank Blair.

In the bloody war which marked the attempt to accomplish this division, Frank Blair played the part of a gallant soldier, but of a soldier whose sword was drawn only against the enemy who stood with arms in his hands. He never pillaged, nor permitted his command to pillage. He fought to secure the supremacy of the Constitution and the perpetuity of the Union. When that was accomplished, he sheathed his sword. So far as he was concerned, the contest was over, the triumph was ended as soon as his opponent lowered his weapon. The moment this was done, he was once more the friend and brother of those against whom he was lately arrayed in deadly strife. In his eyes nothing but necessity justified a resort to arms. And when the necessity was over, all further justification ceased. Those who did not know these convictions of the heroic man whose death we commemorate, can hardly understand his conduct in 1865 and 1866.

While insurrection was in armed resistance to Federal authority, he treated insurrectionists as enemies with whom it was idle to argue, and whom it was necessary to strike down with the deadliest weapons at the command of the national resources. But when resistance ceased, he was transformed from the inexorable enemy of disunionists into the most gracious and indulgent friend of his misguided countrymen, who had ceased to attempt what he regarded in the light of hideous crime. Accordingly, when he returned to St. Louis in 1865, after the close of the war, to find that many thousands of those who had been, and then were his fiercest political enemies, were disfranchised, his first act was to protest energetically against the outrage; to commence in the courts of this State a litigation, the object of which was to demonstrate the illegal character of this disfranchisement, and to enter upon efforts, which did not cease until they were successful, to remove the yoke which rested on the necks of his enemies. All know what he did in 1865, 1866, 1868 and 1870, but few understand the nobleness of his purposes and aims. By many he is supposed to have simply pursued a personal end by means which he considered calculated to attain it. It is considered by a large proportion of mankind that he was, like other political adventurers, aiming at popular favor, by assuming the advocacy of a numerous class. Surely nothing can be more unjust than this. It is contradicted by his whole history. While it was dangerous to avow Republicanism in Missouri, he did not shrink from the avowal. When Republicanism was in the ascendant, and Radicalism under the command of Fremont, commenced its reign of terror and martial law in Missouri, he forsook the dominant party, and exposed himself to obloquy and persecution, nay, to the extremity of personal danger, by withstanding the tyranny of this department commander. When Mr. Chase discriminated against St. Louis and in favor of Chicago and Cincinnati in his treasury regulations, he at once throttled him, and earned for himself all the consequences of that opposition. Returning from the army at the close of a war in which he had commanded a corps, at the head of which he bore back the fiery onset of Hood on the 22d of July 1864, there was no political preferment in Missouri in the gift of the dominant party to which he might not reasonably have aspired. Did he seek to utilize this position? Did he appeal to the dominant party for such preferment? The world knows that he did nothing of the kind. He saw that this party rested upon injustice, against which his soul revolted. He refused to hold any communion with those who were guilty of this injustice. He refused to profit by this iniquity, and ranged himself, not with the powerful oppression, but with the feeble victim of the wrong. He did not confine himself to empty protest. He threw himself into the thick of angry and dangerous contests; and it may be doubted whether, in all the bloody campaign of 1864, he fronted more peril from the casualties of war than he encountered in 1866 from the animosities of those who then held Missouri with the armed hand, and enforced the subjection of her people by military violence—all who remember those days know that he electrified all hearts by his eminently dauntless spirit. The springing valor with which he met and put down the ruffianism by which he was encountered on this memorable occasion, was in its effect on those whose cause he espoused, like that which, in a darker age, would have been ascribed to supernatural influences. It was, indeed, something divine. It was the work of the most precious gift which God makes to humanity—the gift of a heroic spirit which rises to meet a deadly emergency, which grapples with an evil which will otherwise undo a people, and which, by the aid of that power which always helps those who manfully help themselves, achieves the deliverance of mankind.

The gratitude of the State selected Frank Blair to represent Missouri in the Senate of the United States, after he had freed her citizens, in 1870, from the odious discriminations imposed on them by the Radicals of 1865. How well he served the State in that exalted sphere need not be stated here. His acts belong to the history of the country. I have not attempted to chronicle them either in his civil or military career. Time does not permit it, but this much I may say: Frank Blair went into public life a rich man. He left it impoverished and destitute. He was never suspected by the bitterest enemy of unlawfully appropriating to his own use a single penny, either from the treasury of the public, or as a gratuity from those who beset the halls of legislation, and, in one shape or another, give to men in public stations bribes for the betrayal of public duty. He leaves to his children an unspotted name in lieu of a worldly wealth. It is a precious and it is an imperishable inheritance.

Among all the men I have ever known I rank the departed as supreme in generosity and magnanimity. Rancor and malice were foreign to his nature. The moment he had overcome his enemy his own weapons fell from his hands. Anyone who had seen him only when a stern duty was to be performed, when mistaken lenity would have been the greatest cruelty, might imagine that he was all compact of flint and iron. The moment that firmness had done its work and there was no longer occasion for rigor, he was the surest refuge for all who had ceased to resist. To those who had been guilty of wrong and treachery towards himself he was forgiving to a degree which bordered on weakness. It is an honorable distinction that this is the worst censure that can be passed upon his heroic nature.

The events of the last years of General Blair's life have been mentioned by Colonel Gantt in appropriate terms. He did not long hold the position of Collector of Customs, to which he was appointed by President Johnson, but magnanimously yielded it to an old friend. Subsequently, he was Government Railroad Commissioner for the Pacific Railroad.

His short term in the United States Senate was distinguished for the same boldness and honesty of purpose that characterized his earlier congressional career. If he had been more moderate and less honest on some occasions in his utterances, his prospects for the Vice-Presidency would have been more flattering.

With the close of General Blair's senatorial term, his health completely failed. He suffered from a slight attack of paralysis in 1871, but recovered sufficiently to perform his usual duties. A second attack, a year or two later, prostrated him to such an extent that he never recovered. His family indulged the hope that a residence at Clifton Springs, New York, would be beneficial to him. He was taken there, and, for a time, derived some benefit from the waters and pure air of that place. On his return to St. Louis, he showed signs of recovery, and walked the streets again to the great delight of his old friends. Over-exertion, however, both mental and physical, caused a relapse, and he was confined to his house again. His condition grew gradually worse, and, after many remedies had been tried without affording much relief or giving much encouragement to his friends, the process of transfusing blood from a healthy person to his veins was commenced, with beneficial results. It was repeated from time to time, and—Dr. Franklin the attending physician, thinks—would have proved entirely successful had it not been for an accident he met with on the 8th of July. The physician relates the circumstances:

About six o'clock yesterday evening I was called to see him, and found him suffering from the effects of a fall he had received about a quarter past four o'clock in the afternoon. He had been in the habit of walking about his room, and even down stairs. He had been improving rapidly, and the family placed him at the window, supposing he would remain there, while they were down stairs, I suppose, attending to their domestic duties. He was alone in the room but a little while, when he attempted to walk across the floor. In doing so he fell, and, striking his head, received quite a severe blow. He experienced much pain from the concussion, and his paralyzed side was rigid with spasms. He was breathing turgidly and suffering from the effects of coma—unconscious, unable to swallow anything, and the slightest pressure of his hand produced a violent spasm; it was impossible even to touch him. I told the family to watch, knowing he could not live long. At nine o'clock I found his pulse was sinking, and becoming constantly more and more weak—all these symptoms foretelling a fatal termination. General Blair had no apoplexy, but paralysis and softening of the brain. The fall produced a tremendous shock to his system, and probably ruptured vessels in the interior of the brain. That is my diagnosis; there was pressure on the brain, and he died from the effects of compression.

The death of General Blair produced profound regret and sorrow in St. Louis and throughout the country. Meetings were held by the St. Louis Bar, the ex-soldiers of the Missouri Volunteers, the City Council, and other bodies, at which speeches eulogistic of the deceased soldier and statesman were made, and resolutions passed in honor of his memory.

The State Convention, in session at Jefferson City, unanimously adopted the following resolutions:

- That in his death the State of Missouri has lost one of her most useful and eminent citizens, distinguished alike for his private virtues and his brilliant record as a soldier and a patriot.

- That the deceased was strongly marked by the possession of those high qualities which adorn the man, the character of truth, honesty, sincerity, courage and magnanimity, and which justly gave him a firm hold upon the affections and confidence of his fellow countrymen.

- That the dark shadow which the unwelcome messenger, death, has thrown around the domestic circle has awakened our deepest sympathy, and we tender to his venerable parents, his bereaved widow and children, and his numerous friends, our sincere condolence for the irreparable loss which they have sustained.

- That the President of this Convention cause a copy of these resolutions to be presented to the family of the deceased, and with an expression of our sympathies as here set forth.

- That these resolutions be spread upon the journal of this Convention, signed by the President and Secretary, and the public press of the State be requested to publish the same.

- That, in respect to the memory of our departed friend, this Convention do now adjourn to tomorrow at 8 o'clock.

At a meeting of ex-Confederates in St. Louis, the following resolution was adopted:

Resolved, That we, the ex-Confederates here assembled, do as deeply mourn his loss, and as heartily acknowledge his high character and great abilities, as can those who never differed from him in the past great struggle; as soldiers who fought against the cause he espoused, we honor and respect the fidelity, high courage and energy he brought to his aid ; as citizens of Missouri, we recognize the signal service done his State as one of her Senators in the National council; as Americans, we are proud of his manhood; and as men we deplore the loss from among us of one in whom was embodied so much of honor, generosity and gentleness, and we remember with gratitude that so soon as the late civil strife was ended, he was among the first to prove the honesty of his course by welcoming us back as citizens of the Union he had fought to maintain, and that he never thereafter ceased to battle for the restoration and maintenance of our rights under the Constitution.

General Blair's funeral, on Sunday, the nth of July, was attended by a very large concourse of people. All classes were represented, and the public buildings and many private residences displayed emblems of mourning. The services were held at the First Congregational church. Tenth and Locust streets, Dr. Post preaching an eloquent and appropriate discourse. Dr. J. H. Brooks also delivered a short address on the occasion.

General Blair had, a year or two previous to his death, publicly professed the Christian faith, and united with the Presbyterian Church. He left a family consisting of the sorely-bereaved widow, five sons and three daughters, namely: Andrew A., aged twenty-six; Christine, aged twenty-three; James L., aged twenty-one; Frank P., Jr., aged nineteen; George M., aged seventeen; Cora M., aged seven; Evelyn, aged five ; and William Alexander, aged two.

Source:

Reavis, Logan U. “Gen. Francis P. Blair.” In Saint Louis: The Future Great City of the World, 167–80. St. Louis: Gray, Baker & Co, 1875.

Last changed: Nov 19 2018 at 1:05 PM

Back